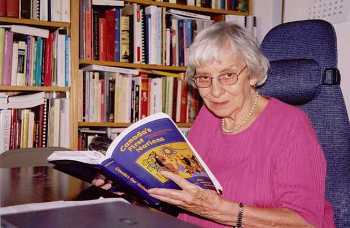

Dr. Olive Dickason (Ottawa Citizen Photograph)Dr. Olive Dickason, a renowned Métis Historian and one of the original members of the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) Cultural Commission, passed away last week at age of 91 from a heart attack.

Dr. Olive Dickason (Ottawa Citizen Photograph)Dr. Olive Dickason, a renowned Métis Historian and one of the original members of the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) Cultural Commission, passed away last week at age of 91 from a heart attack.

When the MNO Cultural Commission was incorporated in 2000, Olive was appointed by the Provisional Council of the MNO to serve as one of its original members. She served on the Commission until 2005. Olive’s academic accomplishments made her a natural and prestigious choice for the Cultural Commission. Prior to Olive, very little was written about Aboriginal history. When she proposed to study Aboriginal history for her Ph. D. dissertation, she met with resistance from the faculty but she became the first academic historian to write about Aboriginal history, an area previously only covered by anthropologists, archaeologists and ethnologists. Before Olive, History dealt almost exclusively with Europeans. Among the honours Olive received were the Order of Canada, a National Aboriginal Achievement Award and several Honourary doctorates.

Olive offers Métis people, especially our young people, a shining example of the kinds of achievements that are within our grasp. She changed the Canadian perspective on Aboriginal people and the MNO is proud of its association with Olive through our Cultural Commission. (More information on Olive’s life and career follow below)

Gary Lipinski

President

Métis Nation of Ontario

A pioneer and a visionary

Created the field of Aboriginal history in Canada

By Louisa Taylor, Ottawa Citizen March 20, 2011

Ottawa’s Olive Dickason wrote groundbreaking histories of Aboriginal Peoples.

Olive Dickason knew what it meant to start over-she did it several times, always with success.

Dickason grew up trapping and fishing in the Manitoba bush during the Depression, then graduated as the only female in a small college in Saskatchewan. She married and had three daughters, then raised them as a single mother while carving out a successful journalism career in the 1950s. Then, when many people are starting to think about retirement, Dickason entered academia and single-handedly created the field of Aboriginal history in Canada, with groundbreaking research into the first contacts between Europeans and First Nations.

“She was a maverick, a pioneer, a visionary,” said her daughter, Anne Dickason.

Olive died last week at the age of 91 following a heart attack. Retired since 1996, the former University of Alberta and University of Ottawa lecturer lived in Centretown for many years, and recently was in a retirement home.

Born in Manitoba to a Métis mother and English father, Dickason worked at the Regina Leader-Post and the Winnipeg Free Press before becoming editor of the women’s section at the Globe and Mail, a position she held until 1967. Dickason was a mentor to many women in the news business, says author Michele Landsberg, whose first job in journalism was working for Dickason at the Globe and Mail.

“Olive was a wonderful, steady, intelligent and supportive editor,” says Landsberg. “She was so elegant and civilized I used to imagine she was a French aristocrat.”

Landsberg recalls Dickason calmly holding her own as the only woman in the rough and tumble of the paper’s news meetings. “She told me once that after every meeting she had to go into the bathroom and cry. They were just so dismissive of her ideas.”

Dickason was a strong role model for her daughters, too, Anne said.

“She was so liberating and so much fun, so hard-working and determined in her goals,” said Anne. “She had a really strong circle of friends. The house was always full of life and laughter.”

It wasn’t always easy.

“Here was a woman with three girls, raising her family on her own in the late 1950s and ’60s, at a time when being a single parent in itself was quite remarkable,” said Anne. “It wasn’t all roses. I remember missing my mother a lot, she was always busy working.”

Dickason was interested in everything -in particular, politics, theatre and literature. The house was often full of friends, many of them important authors of the era. It was during her newspaper days that Dickason first became aware of her Métis roots, after meeting some of her blond, blue-eyed mother’s relatives.

“I just took one look at them and realized there was some family history that hadn’t been discussed,” she once told an interviewer.

When her daughters were almost grown, Dickason decided to explore that interest. At the age of 50, she embarked on first a master’s and then a PhD in history at the University of Ottawa, completed in 1977. When Dickason first proposed to study Aboriginal history for her dissertation, she met with resistance from the faculty.

“Until Olive did her PhD, you had anthropologists, archaeologists and ethnologists who studied the customs of Aboriginal people but not the history -history was considered to be the domain of the Europeans,” said Christine Dernoi, a land claims researcher and friend of Dickason. “Olive broke the mould on that and said ‘Yes, there is indeed a history of First Nations.’ “

Anne Dickason recalls her mother’s “impeccable” research in Paris, Chicago and elsewhere, based on meticulous reading of the original accounts of the first encounters between European explorers and First Nations people. Her bibliographies often ran to more than 100 pages.

Based on that research, Dickason wrote The Myth of the Savage in 1984, and six years later Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples, both of which influenced the study of Canadian history and land claims for years. They remain essential texts: the fourth edition of Canada’s First Nations was published in 2009. Dickason’s work paved the way for generations of Aboriginal academics and demonstrated the importance of First Nations participation in opening up North America, said Dernoi.

“What she succeeded in doing was to show that Canadian history is totally dependent on the presence of the Aboriginal people,” said Dernoi. “The people who lived here knew how to live here -they knew where the food was, where the waterways were, they showed white people how to survive.”

Once she received her PhD, Dickason took a position at the University of Alberta, but all too soon hit the mandatory retirement age of 65 -a seemingly arbitrary law she decided to fight, all the way to the Supreme Court. After Dickason lost that battle, she moved to Ottawa to be near her family and teach at the University of Ottawa as an adjunct professor.

Dernoi met the historian in 1996 when Dickason moderated a community gathering of several hundred people, with the aim of gathering first-person accounts for a First Nations land claim.

“She was wonderful, very patient, very precise, always had to get her facts right,” said Dernoi. “She was very good at eliciting information from other people, respectful and very respected, which is why we had asked for her to be our moderator.”

In spite of her lofty achievements -the Order of Canada, National Aboriginal Achievement Award, several honorary doctorates and more -Dickason remained a fun-loving friend with a self-deprecating sense of humour. According to Anne, when staff at Dickason’s Ottawa retirement home asked what the esteemed academic would like to be called, Olive or Dr. Dickason, “with a lovely smile on her face, she said ‘How about cranky pants?’ “

Dickason is survived by her daughters Anne, Clare and Roberta. A service in her memory was held Thursday at the Beechwood National Memorial Centre.

Read more:

http://www.ottawacitizen.com/pioneer+visionary/4473001/story.html#ixzz1HFCsMKsk

Olive Dickason knew what it meant to start over-she did it several times, always with success.

Olive died last week at the age of 91 following a heart attack. Retired since 1996, the former University of Alberta and University of Ottawa lecturer lived in Centretown for many years, and recently was in a retirement home.

“She was so liberating and so much fun, so hard-working and determined in her goals,” said Anne. “She had a really strong circle of friends. The house was always full of life and laughter.”

“I just took one look at them and realized there was some family history that hadn’t been discussed,” she once told an interviewer.